“No cars to Gulmarg here!” one shouted, as if I’d stepped on his boot.

“No, no, you can’t get a Sumo to Gulmarg,” said a second. “You’ll have to arrange a ride for yourself, cost about 1000 rupees.”

In the short time I’ve known him I’d already imagined killing Farooq in a variety of ways. A new one popped into my head here: running him over with a Sumo NOT on the way to Gulmarg. I gave the condemned a jingle.

“Hello, my darling,” he said in that sweet sing-song of his. “How’s everything going?”

“Not good, Farooq,” I said flatly. “I’m at Karan Nagar and they don’t go to Gulmarg from here.”

“What?” he replied, sounding surprised. “But I just took one from there few months ago. Let me talk to a driver.”

I handed the phone over to the manager of the stand and deciphered from the responses and gestures of the drivers nearby that there were indeed no rides proceeding from this location to my destination.

“What the hell, Farooq?” I said, grabbing the phone. “It’d be nice if when you tell me to go somewhere to get somewhere else you have some idea what you’re talking about.”

After jabbering back and forth we decided that I should hop an auto rickshaw over to the Battmalloo Bus Stop and grab a bus to Gulmarg. Got there and some newspaper-hawking youngster told me that there were Sumos to Tangmarg that went on to Gulmarg. I brightened. He led the way.

Found departing vehicle and hopped aboard. In short order it was full to the brim and the ride commenced, through gorgeous open paddies and tumbledown villages, finally arriving in Tangmarg, the snowy peaks of Gulmarg looming above. Shifted self and stuff over to another Sumo and we were soon on our way there, up and around zigzagging, neck-breaking switchbacks, arriving finally at the gorgeous open expanse surrounded by snow-sprinkled fir trees and beyond them, great white peaks pierced the sky.

I got down, paid the driver and went in search of Abdur Rasheed, the head tourism officer for Gulmarg and my local contact, according to Farooq. The tourist information office was right in front of me, so I strode in and asked about the man I sought.

“He’s over at the offices, at the Gulmarg club,” one told me.

And where is that, I inquired.

“Down that way,” they pointed. “Just keep going straight.”

Looking that way I could see a thin snowy path of sleighs and locals in pherans and a few straggling tourists, but apart from the pointy red-roofed temple, no building for at least half a kilometer. I thought perhaps there might be a faster way, one involving wheels and an engine and comfortable seating, and so went the other direction, towards hotels and shops, to sniff out a ride. No luck, turned back and ended up schlepping it on that sled trail across the snow-covered tundra. A beautiful, sunny day, crisp and fresh and still, and tourists are living it up. Shouting and laughing and throwing snowballs, cannonballing down white hills and jump-jacking snow angels. Looks wonderful, but I’m toting about 70 pounds of bag and computer and clothes and camera for about a mile now and sweating under multiple layers.

Arrive Gulmarg Club to find door locked. As I pee next to the entrance I wonder what to do next. I keep searching grounds and find man in the JKTDC Huts office, who reminds me that all are gone to Friday prayers. Of course. I’d heard the muezzin call but hadn’t realized it was the all-important Friday afternoon event. So I clambered up a small hill to the nearby Lala Restaurant to fill my growling belly and await their return.

Done, I strolled down and into office and found men chatting in a small side office. They called my Abdur Rasheed who instructed them to take the best care of me, and then they placed me into the hands of a pleasant middle-aged local who began walking back the way I’d come but along the opposite route. See, Gulmarg is essentially a big misshapen circle, and in the middle sits a big, open expanse that in the warmer months serves as the world’s highest golf course. In the winter, however, it is an annoyance, an untouched tundra separating one side from another, and one can either walk or be pulled via aging wooden sleds along the northern ridge, as I had originally done, or walk or drive along the longer southern route back to town. Since we had no vehicle and the huts were located more towards the southern edge of town, we screwed up our faces and attacked the southerly path. By the time we arrived at my little green hut nestled up against a thick stand of fir trees nearly thirty minutes later I was drenched in chilly sweat and had over the course of the afternoon walked almost the entire 3.5-km circumference of Gulmarg lugging what now felt like a piano. It was after 4 p.m., and I wanted nothing more than to drop everything and lie down and rest in a quiet, cozy room. But upon entering my hut I found three men milling about my bukhari, a sort of sooty indoor iron furnace that sits in the middle of the room and requires constant feeding of wood. One is the guide who brought me here, and he would soon depart. The other two are comedic geniuses masquerading as my servants. And soon the show would begin.

4:37 p.m., Friday: Fire blazing and warmth spreading its welcoming fingers, my new servants turn to more important matters. “Tea?” asks the one that looks like Robert Duvall with a longshoreman’s cap and a lobotomy. He is Habib. “No, thanks,” I tell him, settling into the loveseat and taking in the gorgeous picture window view. “Coffee?” he inquires. “No, no, I’m fine,” I respond. “Thanks.” As he walks out the other, darker, mustachioed servant enters. This is Majeed, and he is my caretaker, the headman, the one to whom I should turn if ever in need. “You are OK, sir?” “Yes, yes, fine,” I respond. “Everything is good?” he asks. “Yes, good, thanks.” He nods and putters about a bit, prodding the fire with the provided metal pole, dropping a log in. He starts walking towards the door. “Tea?” he asks. “No, thanks,” I say, patience wearing thin. “Coffee?” “No,” I respond a bit more strongly. He departs.

4:47 p.m. I’m flipping through TV stations when in strolls Habib unbidden, brandishing a curly red rubber-covered wire. He mumbles unintelligibly and strolls past me, into the bathroom. Seconds later Majeed comes in to ask what I would be needing during my stay, in terms of food and supplies. I give him a list as Habib walks in and out several times, shaking his head and saying something about the water. List understood, Majeed checks my other door, opposite their kitchen entrance, locks it, turns on some lights, goes into the unused bedroom and checks who knows what. In an attempt to get them out of my room more quickly I go into my bedroom bathroom to check on Habib, who is making a hubbub over a giant black tub of water balanced precariously on a rough wood crate. Wires stick into two wall-socket holes and then wind their way into the great tub and directly into the water, where it is hoped their searing ends will transfer heat to the water, which would then be used for bathing. After 15 minutes, the two reluctantly depart.

(Here is Habib’s jerry-rigged, electric shock-death waiting to happen device that actually did the trick.)

5:21 p.m.: Majeed pops his head in, “would you like tea, sir?” I look up from my computer. “Coffee?” No, goddammit, I don’t. I want to lock the door. And I do just that.

6:04 p.m.: A push from the far side of the kitchen door finds it locked, and an unintelligible shout follows. “Yes?” I inquire to the unseen man. “Dinner, sir?” No, not yet, thanks. “Dinner? Time?” Majeed inquires again. Oh. I go over to the door and open it and tell him 8:30. “OK, very good,” and he turns and starts to walk away, and then, “Tea?” No, I reply. “Coffee?” I offer a wan smile and he gets the drift, walks back into kitchen and nearly two hours after arrival I have cleared some space for solitude, a pleasant two and a half hours before the bopsey twins are again scheduled to intrude.

6:29: Watching Deutsch Welle, Germany’s inept stab at a BBC and the only occasionally English-language channel this bare-bones satellite service offers. The room has warmed nicely but my feet and ankle regions remain chilly. I notice that the ends of my pant-legs are still wet from mushing through the snow. I take them off and hang them on the bukhari. They should be dry in no time, I think to myself, settling back into the loveseat just in time to catch some poor cute fraulein financial reporter butchering my mother tongue.

6:34 p.m. Remove jeans from bukhari to find two jagged black burn spots near the knees. They crack and split open. These are the only pants I brought with me. I will for the next two days walk around looking from the waist down like a man narrowly escaped from a raging fire.

7:33 p.m.: Habib, who speaks and understands all of four English words, is at the door shouting something in Kashmiri. I shout back but it’s no use, he needs to see my face. I get up and open the door. “Dinner?” “Uhh, no, not yet,” I shake my head in awe, wondering if these two ever speak to each other or just go about their tasks independent of one another, each believing himself to be the true arbiter of tea and meal times. He looks at me blankly for two or three seconds, then repeats, perfectly deadpan, “Dinner?” I’m not a man of great patience; I stifle the urge to slap him. “In one hour, please.” “Huh, uh, uu,” he stammers, light dawning slowly. “Hour?” “Yes, yes,” I confirm, “Around 8:30 would be good.” “OK,” he says, looking rather stunned.

8:41 p.m.: Dinner is served, in tandem. Habib bringing in a place setting, then a platter of rice. Majeed brings in meat and vegetables, then inquires if I need bread. No. I begin to eat.

8:44 p.m.: Habib opens door, looks at me. “Yes?” I ask. He comes towards me. “No, no, everything is fine, thanks,” I tell him. He stops. Looks. Scratches his head through his wool hat. Majeed appears at the door, looks concerned askance at the two of us as if we’d secretly been plotting his demise. “The food is very good,” I tell them. “Very good.” They exit and shut door.

8:55 p.m.: Door opens and Habib stands there. The plates are stacked next to me at computer. He looks, says something that I assume is a query regarding my completion of meal. I nod. He clears dishes and I help, telling them that dinner was very good. “Breakfast time?” Majeed asks, thinking ahead. “8:30,” I say. “OK, 8:30,” Majeed confirms, and the two busy themselves with cleaning up.

8:27 a.m., Saturday: I have been up reading for about forty minutes and haven’t heard a peep from the kitchen. I peer in and find an empty room. I close door and return to reading.

8:44 a.m. Habib walks in and begins to restart the bukhari, loading it with wood. “Good morning, Sir!” “Good morning,” I respond. “Tea?” he asks, then quickly, “Coffee?” “Yes,” I say as he is spitting out the second question. He walks out.

8:57 a.m. I open kitchen door. “Which are you making, tea or coffee?” “Coffee,” Habib answers without looking up at me. Good to know.

9:03 a.m. Habib walks in, puts down pot and sugar and cup with saucer. Majeed appears. “Omelette?” he asks. “Do you have any fruit, or yogurt,” I ask, using the Kashmiri nouns. “Oh, no, no,” he responds gravely. These items were on yesterday’s list. “And what happened to 8:30 breakfast?” I ask. He asks Habib for the time. “Oh, yes,” he stammers, attempts a smile with Habib looking on accusatorily. “Omelette?” Indeed.

9:16 a.m. Habib brings in bread with butter and jam. Majeed drops off a glistening omelette. I’m all set and start to dig in. As they retreat to kitchen they stop and turn. “Bread?” asks Habib. I have two very large and untouched hunks of fresh Kashmiri bread before me. This man placed them there about 9 seconds previous. “Another omelette?” queries Majeed, although the one he just made sits still whole where he placed not a minute before. I almost spit out my coffee and stare at them in wonder. “Omelette?” “More bread?” they ask again in earnest. “No, no” I tell them. “No, thank you,” shaking my head. They look at each other. They look at me. “Go,” I tell them, pointing to the door. “Please go.” Exit help stage right.

10:42 a.m. The breakfast dishes were cleared about half an hour ago. I am at the computer jotting down some notes. Habib opens the door and stands there looking at me. “Tea?” he asks. I beg you, dear reader, what does one do with such needy servitude? “Coffee?” he prods. “NO!” I nearly shout. But really.

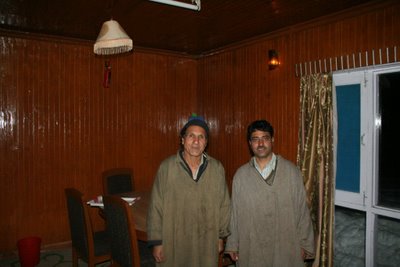

Making their curtain call, the players in this mind-bogglingly stumbly pas de trios: Habib on left, Majeed on right.