or, How I Started Worrying and Moved to Rajbagh

(Sorry, wrote this quickly cuz I wanted to get it in 'fore I left for vacation. Not terribly entertaining, but rather informative and slightly suspenseful I'd hope.)

“So, where are you?” Sajjad asks when I call after returning from Gulmarg on Sunday morning.

“I’m back in Srinagar, Lal Chowk” I tell him. “Just arrived.”

“Oh, OK,” he says. “I was just at your house.”

“Oh, too bad I missed you.”

“Yes, I was talking to Iftikhar,” he says. “There is something we should discuss.”

“Oh, yeah, what is it?” I responded, wondering what it could be.

“No, no, I will tell you later,” he said, sounding serious.

“OK, we’ll talk tomorrow.”

“Yes, tomorrow morning,” he agreed. “Alright, fine.”

In the five months I’ve worked for him, Sajad has never told once told me that we needed to talk, so this little conversation sets the wheels spinning. He has said several times how he is tired and would like very much to quit the paper and retire. Could this be it, the end of Kashmir Observer? Could I be unemployed by tomorrow? It seems unlikely, but I count it among the possibilities. Another is that it has to do with Hussain, mine and Iftikhar’s servant. Dissatisfied with his work of late, Iftikhar had a few weeks ago told Hussain that he (Iftikhar) would be letting him (Hussain) go at the end of November. Sajad and I spoke and decided that we would try to settle the matter so that Hussain would continue to work as my cook -- for which Sajad and I would share the payment of his salary -- and as Iftikhar’s gardener in return for housing. Perhaps some new development had occurred on that end.

So these were the thoughts that were bouncing around in my head when Sajad came online later that evening and I asked him what was up. He said that it was important and that it concerned all of us, but that it was nothing to worry about and that we’d discuss it tomorrow.

The next day I get to the office and was waiting, waiting, waiting. He finally arrives at about 2:30 and we go into the sitting room to chat.

“OK,” he begins, in that long, drawn out way he has. “There were some visitors to your house on Friday night. Three men. Armed. Militants.”

He looks at me sharply and I move not a muscle. He continues.

“Apparently they knocked on your window first,” he says. “You were gone and they received no response, of course, then they knocked on Hussain’s window and he woke up and they told him they wanted a place to sleep.”

What?! Fast forward to later on, when I went home and found Hussain in the kitchen cooking my dinner.

“So we had some visitors, I hear,” I say, hoping he gets the drift.

“What?”

“Sajjad told me about the militants that were here, Friday night?”

“Oh, yeah!” he said, screwing up his face and sticking a ladle into the pot.

“So tell me about it. Did they knock on my window first?”

“Yeah, they knock your window and I hear something and look out. I see them and they come over and ask for place to rest for a while,” he said.

“I let them inside and two of them fell asleep but the other, the commander, he stayed awake.”

“The Kashmiri?” I asked, trying to get a sense of who was in charge, their mission, etc.

“The Kashmiri was sleeping first!” he shot back. “He out right away. NOooooo, commander big, strong Pakistani. Like this,” and he lifts up his shoulders and arms like a gorilla.

“He told me that it was bad that I was working for this man, as a servant. Asked me why I’m not fighting for my home. I told him I working!

“He said that I should join the movement. Told me if I ever needed anything I should give him call.”

“He gave you his phone number?” I asked, incredulous. This seemed a breach of militant etiquette.

“Yeah, his mobile number.”

I stood there scratching my head and wondering what it all meant. My home suddenly seemed less homey.

“They had so many guns…big, militant guns and six pistols!” Hussein resumed, getting jumpy. “But next time they come, I killing them!

So, yes, three militants paid a visit to the compound while I was working in Gulmarg late last month. Apparently they knocked on my window first, which could mean they knew there was a foreigner living there and wanted something with him – to kidnap and use as leverage or for ransom or who knows what – or could have just been dumb luck and they had no idea who lived where. The fact that the commander felt comfortable enough to give Hussain his phone number seemed to suggest that they had had no nasty plan. Either way, from that point on I didn’t feel terribly comfortable bedding down in the dark mere feet away from the window to which large, armed Pakistani militants had come a-calling all too recently. So, at Sajjad’s suggestion, I hurriedly looked for other lodgings, preferably somewhere closer to town, somewhere safer, and somewhere with 24-hour power supply. After a few days’ search I found a too-large, too-expensive place in Rajbagh, a pleasant, army-infested neighborhood just across the Jhelum from the Kashmir Observer office, and snatched it up. Best of all, it has a hamam, a uniquely Kashmiri little room under which one lights and then closes a (outside) metal door on a fire, thus heating the concrete for about 15 hours. It’s warming my buns as I write on this fine, chilly Christmas night, and all is well again in Kashmir.

Seasons Greetings. I'm off to Delhi tomorrow, then various parts of Thailand and India for about a month-long break.

Best,

D

A focus on urbanism and cities, particularly the sprawling beauty formerly known as Constantinople. Also meanderings into Islam, media, technology, and sustainability, with occasional musings on sports, anecdotes and personal tidbits.

12.26.2006

11.27.2006

From Gulmarg, with Patience

M. Farooq Shah is known for many things, and his reliability regarding making a muck of travel plans is one of them. So it was last Friday morning when, as per Farooq’s guidance, I arrived at the Karan Nagar Sumo stand bright and early and asked a few local gents to point me towards the next vehicle departing for Gulmarg, a wintry, Rocky Mountain-like wonderland where I’d planned to do some reporting.

“No cars to Gulmarg here!” one shouted, as if I’d stepped on his boot.

“No, no, you can’t get a Sumo to Gulmarg,” said a second. “You’ll have to arrange a ride for yourself, cost about 1000 rupees.”

In the short time I’ve known him I’d already imagined killing Farooq in a variety of ways. A new one popped into my head here: running him over with a Sumo NOT on the way to Gulmarg. I gave the condemned a jingle.

“Hello, my darling,” he said in that sweet sing-song of his. “How’s everything going?”

“Not good, Farooq,” I said flatly. “I’m at Karan Nagar and they don’t go to Gulmarg from here.”

“What?” he replied, sounding surprised. “But I just took one from there few months ago. Let me talk to a driver.”

I handed the phone over to the manager of the stand and deciphered from the responses and gestures of the drivers nearby that there were indeed no rides proceeding from this location to my destination.

“What the hell, Farooq?” I said, grabbing the phone. “It’d be nice if when you tell me to go somewhere to get somewhere else you have some idea what you’re talking about.”

After jabbering back and forth we decided that I should hop an auto rickshaw over to the Battmalloo Bus Stop and grab a bus to Gulmarg. Got there and some newspaper-hawking youngster told me that there were Sumos to Tangmarg that went on to Gulmarg. I brightened. He led the way.

Found departing vehicle and hopped aboard. In short order it was full to the brim and the ride commenced, through gorgeous open paddies and tumbledown villages, finally arriving in Tangmarg, the snowy peaks of Gulmarg looming above. Shifted self and stuff over to another Sumo and we were soon on our way there, up and around zigzagging, neck-breaking switchbacks, arriving finally at the gorgeous open expanse surrounded by snow-sprinkled fir trees and beyond them, great white peaks pierced the sky.

I got down, paid the driver and went in search of Abdur Rasheed, the head tourism officer for Gulmarg and my local contact, according to Farooq. The tourist information office was right in front of me, so I strode in and asked about the man I sought.

“He’s over at the offices, at the Gulmarg club,” one told me.

And where is that, I inquired.

“Down that way,” they pointed. “Just keep going straight.”

Looking that way I could see a thin snowy path of sleighs and locals in pherans and a few straggling tourists, but apart from the pointy red-roofed temple, no building for at least half a kilometer. I thought perhaps there might be a faster way, one involving wheels and an engine and comfortable seating, and so went the other direction, towards hotels and shops, to sniff out a ride. No luck, turned back and ended up schlepping it on that sled trail across the snow-covered tundra. A beautiful, sunny day, crisp and fresh and still, and tourists are living it up. Shouting and laughing and throwing snowballs, cannonballing down white hills and jump-jacking snow angels. Looks wonderful, but I’m toting about 70 pounds of bag and computer and clothes and camera for about a mile now and sweating under multiple layers.

Arrive Gulmarg Club to find door locked. As I pee next to the entrance I wonder what to do next. I keep searching grounds and find man in the JKTDC Huts office, who reminds me that all are gone to Friday prayers. Of course. I’d heard the muezzin call but hadn’t realized it was the all-important Friday afternoon event. So I clambered up a small hill to the nearby Lala Restaurant to fill my growling belly and await their return.

Done, I strolled down and into office and found men chatting in a small side office. They called my Abdur Rasheed who instructed them to take the best care of me, and then they placed me into the hands of a pleasant middle-aged local who began walking back the way I’d come but along the opposite route. See, Gulmarg is essentially a big misshapen circle, and in the middle sits a big, open expanse that in the warmer months serves as the world’s highest golf course. In the winter, however, it is an annoyance, an untouched tundra separating one side from another, and one can either walk or be pulled via aging wooden sleds along the northern ridge, as I had originally done, or walk or drive along the longer southern route back to town. Since we had no vehicle and the huts were located more towards the southern edge of town, we screwed up our faces and attacked the southerly path. By the time we arrived at my little green hut nestled up against a thick stand of fir trees nearly thirty minutes later I was drenched in chilly sweat and had over the course of the afternoon walked almost the entire 3.5-km circumference of Gulmarg lugging what now felt like a piano. It was after 4 p.m., and I wanted nothing more than to drop everything and lie down and rest in a quiet, cozy room. But upon entering my hut I found three men milling about my bukhari, a sort of sooty indoor iron furnace that sits in the middle of the room and requires constant feeding of wood. One is the guide who brought me here, and he would soon depart. The other two are comedic geniuses masquerading as my servants. And soon the show would begin.

4:37 p.m., Friday: Fire blazing and warmth spreading its welcoming fingers, my new servants turn to more important matters. “Tea?” asks the one that looks like Robert Duvall with a longshoreman’s cap and a lobotomy. He is Habib. “No, thanks,” I tell him, settling into the loveseat and taking in the gorgeous picture window view. “Coffee?” he inquires. “No, no, I’m fine,” I respond. “Thanks.” As he walks out the other, darker, mustachioed servant enters. This is Majeed, and he is my caretaker, the headman, the one to whom I should turn if ever in need. “You are OK, sir?” “Yes, yes, fine,” I respond. “Everything is good?” he asks. “Yes, good, thanks.” He nods and putters about a bit, prodding the fire with the provided metal pole, dropping a log in. He starts walking towards the door. “Tea?” he asks. “No, thanks,” I say, patience wearing thin. “Coffee?” “No,” I respond a bit more strongly. He departs.

4:47 p.m. I’m flipping through TV stations when in strolls Habib unbidden, brandishing a curly red rubber-covered wire. He mumbles unintelligibly and strolls past me, into the bathroom. Seconds later Majeed comes in to ask what I would be needing during my stay, in terms of food and supplies. I give him a list as Habib walks in and out several times, shaking his head and saying something about the water. List understood, Majeed checks my other door, opposite their kitchen entrance, locks it, turns on some lights, goes into the unused bedroom and checks who knows what. In an attempt to get them out of my room more quickly I go into my bedroom bathroom to check on Habib, who is making a hubbub over a giant black tub of water balanced precariously on a rough wood crate. Wires stick into two wall-socket holes and then wind their way into the great tub and directly into the water, where it is hoped their searing ends will transfer heat to the water, which would then be used for bathing. After 15 minutes, the two reluctantly depart.

(Here is Habib’s jerry-rigged, electric shock-death waiting to happen device that actually did the trick.)

5:21 p.m.: Majeed pops his head in, “would you like tea, sir?” I look up from my computer. “Coffee?” No, goddammit, I don’t. I want to lock the door. And I do just that.

6:04 p.m.: A push from the far side of the kitchen door finds it locked, and an unintelligible shout follows. “Yes?” I inquire to the unseen man. “Dinner, sir?” No, not yet, thanks. “Dinner? Time?” Majeed inquires again. Oh. I go over to the door and open it and tell him 8:30. “OK, very good,” and he turns and starts to walk away, and then, “Tea?” No, I reply. “Coffee?” I offer a wan smile and he gets the drift, walks back into kitchen and nearly two hours after arrival I have cleared some space for solitude, a pleasant two and a half hours before the bopsey twins are again scheduled to intrude.

6:29: Watching Deutsch Welle, Germany’s inept stab at a BBC and the only occasionally English-language channel this bare-bones satellite service offers. The room has warmed nicely but my feet and ankle regions remain chilly. I notice that the ends of my pant-legs are still wet from mushing through the snow. I take them off and hang them on the bukhari. They should be dry in no time, I think to myself, settling back into the loveseat just in time to catch some poor cute fraulein financial reporter butchering my mother tongue.

6:34 p.m. Remove jeans from bukhari to find two jagged black burn spots near the knees. They crack and split open. These are the only pants I brought with me. I will for the next two days walk around looking from the waist down like a man narrowly escaped from a raging fire.

7:33 p.m.: Habib, who speaks and understands all of four English words, is at the door shouting something in Kashmiri. I shout back but it’s no use, he needs to see my face. I get up and open the door. “Dinner?” “Uhh, no, not yet,” I shake my head in awe, wondering if these two ever speak to each other or just go about their tasks independent of one another, each believing himself to be the true arbiter of tea and meal times. He looks at me blankly for two or three seconds, then repeats, perfectly deadpan, “Dinner?” I’m not a man of great patience; I stifle the urge to slap him. “In one hour, please.” “Huh, uh, uu,” he stammers, light dawning slowly. “Hour?” “Yes, yes,” I confirm, “Around 8:30 would be good.” “OK,” he says, looking rather stunned.

8:41 p.m.: Dinner is served, in tandem. Habib bringing in a place setting, then a platter of rice. Majeed brings in meat and vegetables, then inquires if I need bread. No. I begin to eat.

8:44 p.m.: Habib opens door, looks at me. “Yes?” I ask. He comes towards me. “No, no, everything is fine, thanks,” I tell him. He stops. Looks. Scratches his head through his wool hat. Majeed appears at the door, looks concerned askance at the two of us as if we’d secretly been plotting his demise. “The food is very good,” I tell them. “Very good.” They exit and shut door.

8:55 p.m.: Door opens and Habib stands there. The plates are stacked next to me at computer. He looks, says something that I assume is a query regarding my completion of meal. I nod. He clears dishes and I help, telling them that dinner was very good. “Breakfast time?” Majeed asks, thinking ahead. “8:30,” I say. “OK, 8:30,” Majeed confirms, and the two busy themselves with cleaning up.

8:27 a.m., Saturday: I have been up reading for about forty minutes and haven’t heard a peep from the kitchen. I peer in and find an empty room. I close door and return to reading.

8:44 a.m. Habib walks in and begins to restart the bukhari, loading it with wood. “Good morning, Sir!” “Good morning,” I respond. “Tea?” he asks, then quickly, “Coffee?” “Yes,” I say as he is spitting out the second question. He walks out.

8:57 a.m. I open kitchen door. “Which are you making, tea or coffee?” “Coffee,” Habib answers without looking up at me. Good to know.

9:03 a.m. Habib walks in, puts down pot and sugar and cup with saucer. Majeed appears. “Omelette?” he asks. “Do you have any fruit, or yogurt,” I ask, using the Kashmiri nouns. “Oh, no, no,” he responds gravely. These items were on yesterday’s list. “And what happened to 8:30 breakfast?” I ask. He asks Habib for the time. “Oh, yes,” he stammers, attempts a smile with Habib looking on accusatorily. “Omelette?” Indeed.

9:16 a.m. Habib brings in bread with butter and jam. Majeed drops off a glistening omelette. I’m all set and start to dig in. As they retreat to kitchen they stop and turn. “Bread?” asks Habib. I have two very large and untouched hunks of fresh Kashmiri bread before me. This man placed them there about 9 seconds previous. “Another omelette?” queries Majeed, although the one he just made sits still whole where he placed not a minute before. I almost spit out my coffee and stare at them in wonder. “Omelette?” “More bread?” they ask again in earnest. “No, no” I tell them. “No, thank you,” shaking my head. They look at each other. They look at me. “Go,” I tell them, pointing to the door. “Please go.” Exit help stage right.

10:42 a.m. The breakfast dishes were cleared about half an hour ago. I am at the computer jotting down some notes. Habib opens the door and stands there looking at me. “Tea?” he asks. I beg you, dear reader, what does one do with such needy servitude? “Coffee?” he prods. “NO!” I nearly shout. But really.

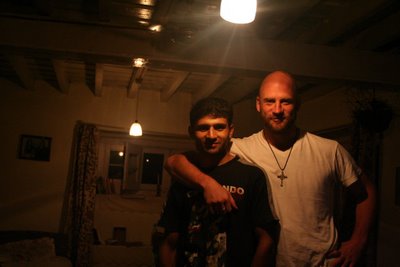

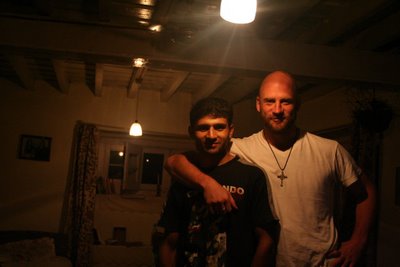

Making their curtain call, the players in this mind-bogglingly stumbly pas de trios: Habib on left, Majeed on right.

“No cars to Gulmarg here!” one shouted, as if I’d stepped on his boot.

“No, no, you can’t get a Sumo to Gulmarg,” said a second. “You’ll have to arrange a ride for yourself, cost about 1000 rupees.”

In the short time I’ve known him I’d already imagined killing Farooq in a variety of ways. A new one popped into my head here: running him over with a Sumo NOT on the way to Gulmarg. I gave the condemned a jingle.

“Hello, my darling,” he said in that sweet sing-song of his. “How’s everything going?”

“Not good, Farooq,” I said flatly. “I’m at Karan Nagar and they don’t go to Gulmarg from here.”

“What?” he replied, sounding surprised. “But I just took one from there few months ago. Let me talk to a driver.”

I handed the phone over to the manager of the stand and deciphered from the responses and gestures of the drivers nearby that there were indeed no rides proceeding from this location to my destination.

“What the hell, Farooq?” I said, grabbing the phone. “It’d be nice if when you tell me to go somewhere to get somewhere else you have some idea what you’re talking about.”

After jabbering back and forth we decided that I should hop an auto rickshaw over to the Battmalloo Bus Stop and grab a bus to Gulmarg. Got there and some newspaper-hawking youngster told me that there were Sumos to Tangmarg that went on to Gulmarg. I brightened. He led the way.

Found departing vehicle and hopped aboard. In short order it was full to the brim and the ride commenced, through gorgeous open paddies and tumbledown villages, finally arriving in Tangmarg, the snowy peaks of Gulmarg looming above. Shifted self and stuff over to another Sumo and we were soon on our way there, up and around zigzagging, neck-breaking switchbacks, arriving finally at the gorgeous open expanse surrounded by snow-sprinkled fir trees and beyond them, great white peaks pierced the sky.

I got down, paid the driver and went in search of Abdur Rasheed, the head tourism officer for Gulmarg and my local contact, according to Farooq. The tourist information office was right in front of me, so I strode in and asked about the man I sought.

“He’s over at the offices, at the Gulmarg club,” one told me.

And where is that, I inquired.

“Down that way,” they pointed. “Just keep going straight.”

Looking that way I could see a thin snowy path of sleighs and locals in pherans and a few straggling tourists, but apart from the pointy red-roofed temple, no building for at least half a kilometer. I thought perhaps there might be a faster way, one involving wheels and an engine and comfortable seating, and so went the other direction, towards hotels and shops, to sniff out a ride. No luck, turned back and ended up schlepping it on that sled trail across the snow-covered tundra. A beautiful, sunny day, crisp and fresh and still, and tourists are living it up. Shouting and laughing and throwing snowballs, cannonballing down white hills and jump-jacking snow angels. Looks wonderful, but I’m toting about 70 pounds of bag and computer and clothes and camera for about a mile now and sweating under multiple layers.

Arrive Gulmarg Club to find door locked. As I pee next to the entrance I wonder what to do next. I keep searching grounds and find man in the JKTDC Huts office, who reminds me that all are gone to Friday prayers. Of course. I’d heard the muezzin call but hadn’t realized it was the all-important Friday afternoon event. So I clambered up a small hill to the nearby Lala Restaurant to fill my growling belly and await their return.

Done, I strolled down and into office and found men chatting in a small side office. They called my Abdur Rasheed who instructed them to take the best care of me, and then they placed me into the hands of a pleasant middle-aged local who began walking back the way I’d come but along the opposite route. See, Gulmarg is essentially a big misshapen circle, and in the middle sits a big, open expanse that in the warmer months serves as the world’s highest golf course. In the winter, however, it is an annoyance, an untouched tundra separating one side from another, and one can either walk or be pulled via aging wooden sleds along the northern ridge, as I had originally done, or walk or drive along the longer southern route back to town. Since we had no vehicle and the huts were located more towards the southern edge of town, we screwed up our faces and attacked the southerly path. By the time we arrived at my little green hut nestled up against a thick stand of fir trees nearly thirty minutes later I was drenched in chilly sweat and had over the course of the afternoon walked almost the entire 3.5-km circumference of Gulmarg lugging what now felt like a piano. It was after 4 p.m., and I wanted nothing more than to drop everything and lie down and rest in a quiet, cozy room. But upon entering my hut I found three men milling about my bukhari, a sort of sooty indoor iron furnace that sits in the middle of the room and requires constant feeding of wood. One is the guide who brought me here, and he would soon depart. The other two are comedic geniuses masquerading as my servants. And soon the show would begin.

4:37 p.m., Friday: Fire blazing and warmth spreading its welcoming fingers, my new servants turn to more important matters. “Tea?” asks the one that looks like Robert Duvall with a longshoreman’s cap and a lobotomy. He is Habib. “No, thanks,” I tell him, settling into the loveseat and taking in the gorgeous picture window view. “Coffee?” he inquires. “No, no, I’m fine,” I respond. “Thanks.” As he walks out the other, darker, mustachioed servant enters. This is Majeed, and he is my caretaker, the headman, the one to whom I should turn if ever in need. “You are OK, sir?” “Yes, yes, fine,” I respond. “Everything is good?” he asks. “Yes, good, thanks.” He nods and putters about a bit, prodding the fire with the provided metal pole, dropping a log in. He starts walking towards the door. “Tea?” he asks. “No, thanks,” I say, patience wearing thin. “Coffee?” “No,” I respond a bit more strongly. He departs.

4:47 p.m. I’m flipping through TV stations when in strolls Habib unbidden, brandishing a curly red rubber-covered wire. He mumbles unintelligibly and strolls past me, into the bathroom. Seconds later Majeed comes in to ask what I would be needing during my stay, in terms of food and supplies. I give him a list as Habib walks in and out several times, shaking his head and saying something about the water. List understood, Majeed checks my other door, opposite their kitchen entrance, locks it, turns on some lights, goes into the unused bedroom and checks who knows what. In an attempt to get them out of my room more quickly I go into my bedroom bathroom to check on Habib, who is making a hubbub over a giant black tub of water balanced precariously on a rough wood crate. Wires stick into two wall-socket holes and then wind their way into the great tub and directly into the water, where it is hoped their searing ends will transfer heat to the water, which would then be used for bathing. After 15 minutes, the two reluctantly depart.

(Here is Habib’s jerry-rigged, electric shock-death waiting to happen device that actually did the trick.)

5:21 p.m.: Majeed pops his head in, “would you like tea, sir?” I look up from my computer. “Coffee?” No, goddammit, I don’t. I want to lock the door. And I do just that.

6:04 p.m.: A push from the far side of the kitchen door finds it locked, and an unintelligible shout follows. “Yes?” I inquire to the unseen man. “Dinner, sir?” No, not yet, thanks. “Dinner? Time?” Majeed inquires again. Oh. I go over to the door and open it and tell him 8:30. “OK, very good,” and he turns and starts to walk away, and then, “Tea?” No, I reply. “Coffee?” I offer a wan smile and he gets the drift, walks back into kitchen and nearly two hours after arrival I have cleared some space for solitude, a pleasant two and a half hours before the bopsey twins are again scheduled to intrude.

6:29: Watching Deutsch Welle, Germany’s inept stab at a BBC and the only occasionally English-language channel this bare-bones satellite service offers. The room has warmed nicely but my feet and ankle regions remain chilly. I notice that the ends of my pant-legs are still wet from mushing through the snow. I take them off and hang them on the bukhari. They should be dry in no time, I think to myself, settling back into the loveseat just in time to catch some poor cute fraulein financial reporter butchering my mother tongue.

6:34 p.m. Remove jeans from bukhari to find two jagged black burn spots near the knees. They crack and split open. These are the only pants I brought with me. I will for the next two days walk around looking from the waist down like a man narrowly escaped from a raging fire.

7:33 p.m.: Habib, who speaks and understands all of four English words, is at the door shouting something in Kashmiri. I shout back but it’s no use, he needs to see my face. I get up and open the door. “Dinner?” “Uhh, no, not yet,” I shake my head in awe, wondering if these two ever speak to each other or just go about their tasks independent of one another, each believing himself to be the true arbiter of tea and meal times. He looks at me blankly for two or three seconds, then repeats, perfectly deadpan, “Dinner?” I’m not a man of great patience; I stifle the urge to slap him. “In one hour, please.” “Huh, uh, uu,” he stammers, light dawning slowly. “Hour?” “Yes, yes,” I confirm, “Around 8:30 would be good.” “OK,” he says, looking rather stunned.

8:41 p.m.: Dinner is served, in tandem. Habib bringing in a place setting, then a platter of rice. Majeed brings in meat and vegetables, then inquires if I need bread. No. I begin to eat.

8:44 p.m.: Habib opens door, looks at me. “Yes?” I ask. He comes towards me. “No, no, everything is fine, thanks,” I tell him. He stops. Looks. Scratches his head through his wool hat. Majeed appears at the door, looks concerned askance at the two of us as if we’d secretly been plotting his demise. “The food is very good,” I tell them. “Very good.” They exit and shut door.

8:55 p.m.: Door opens and Habib stands there. The plates are stacked next to me at computer. He looks, says something that I assume is a query regarding my completion of meal. I nod. He clears dishes and I help, telling them that dinner was very good. “Breakfast time?” Majeed asks, thinking ahead. “8:30,” I say. “OK, 8:30,” Majeed confirms, and the two busy themselves with cleaning up.

8:27 a.m., Saturday: I have been up reading for about forty minutes and haven’t heard a peep from the kitchen. I peer in and find an empty room. I close door and return to reading.

8:44 a.m. Habib walks in and begins to restart the bukhari, loading it with wood. “Good morning, Sir!” “Good morning,” I respond. “Tea?” he asks, then quickly, “Coffee?” “Yes,” I say as he is spitting out the second question. He walks out.

8:57 a.m. I open kitchen door. “Which are you making, tea or coffee?” “Coffee,” Habib answers without looking up at me. Good to know.

9:03 a.m. Habib walks in, puts down pot and sugar and cup with saucer. Majeed appears. “Omelette?” he asks. “Do you have any fruit, or yogurt,” I ask, using the Kashmiri nouns. “Oh, no, no,” he responds gravely. These items were on yesterday’s list. “And what happened to 8:30 breakfast?” I ask. He asks Habib for the time. “Oh, yes,” he stammers, attempts a smile with Habib looking on accusatorily. “Omelette?” Indeed.

9:16 a.m. Habib brings in bread with butter and jam. Majeed drops off a glistening omelette. I’m all set and start to dig in. As they retreat to kitchen they stop and turn. “Bread?” asks Habib. I have two very large and untouched hunks of fresh Kashmiri bread before me. This man placed them there about 9 seconds previous. “Another omelette?” queries Majeed, although the one he just made sits still whole where he placed not a minute before. I almost spit out my coffee and stare at them in wonder. “Omelette?” “More bread?” they ask again in earnest. “No, no” I tell them. “No, thank you,” shaking my head. They look at each other. They look at me. “Go,” I tell them, pointing to the door. “Please go.” Exit help stage right.

10:42 a.m. The breakfast dishes were cleared about half an hour ago. I am at the computer jotting down some notes. Habib opens the door and stands there looking at me. “Tea?” he asks. I beg you, dear reader, what does one do with such needy servitude? “Coffee?” he prods. “NO!” I nearly shout. But really.

Making their curtain call, the players in this mind-bogglingly stumbly pas de trios: Habib on left, Majeed on right.

11.12.2006

Is There A Window Open?

No, that's just Kashmir in November.

Hello, again. I haven’t updated in a while not because I’ve been too terribly busy but more because nothing terribly noteworthy had happened. Sure, I took a little detour to Turkey, which was really something, and just before that I enjoyed a wonderful dinner celebration for Agha’s 84th birthday, an evening during which I chatted with an amiable Delhi University professor who’d been tortured for thirty days and then sat on death row for about a year. But nothing really smashing, at least in my mind. Or maybe I’ve just been lazy.

Either way, the torporing doldrums ended this evening shortly after dinner. But first I have to back up a bit. Ever since I began to even consider the possibility of moving to and living in Kashmir I had heard tell of its fierce winters, of bitter cold nights that lasted a lifetime, of entire villages buried in snow, of roads closed, of frozen guns unable to fire, of the long-winded trials of a frigid Himalayan season in a region without indoor heating. Upon hearing that I planned to live in Kashmir an entire year, Rafiq Kathwari, a Kashmiri journalist cum photo-documentarian who now spends much of his time in New York, bluntly warned: “You’re staying there during the winter? You will die.” But as September waned the days were still warm, and then October brought little change: the sun still shone nearly every day and even if the nights had grown chilly the rising of the mercury became as reliable as that of the sun. That is until these last few days. The sun has taken a siesta. The Kashmiri pheran, a long, roomy dun-colored overcoat-poncho, has become ubiquitous. By the time I arrive home from work in the evenings after the ten minute bike ride my hands are nearly numb. And then this morning I saw a man maneuvering something unseen under his pheran, and when I walked closely past him I felt its warmth: a kangri! The mythical earthenware pot that Kashmiris hold underneath their outer coverings during the winter months, it holds perennially burning coals and is generally a substitute for what the developed world all but ignores: heating. The slang term is winterwife, a phrase that sounds much more pregnant in Kashmiri. But these things I shrugged off, girding myself for what still lie ahead. (And truth be told I haven’t heard a temperature number in months. But even if I had, it’s in Celsius, so 13, for instance, what does that mean? Sure, I could do the math, but I know offhand that it’s not the 13 of a Wisconsin November, I can tell you that much. It’s just nicely nestled in there somewhere between hot and cold, between pleasant and less so, between summer and winter. Cool. Sweater weather, as they say.) And of course I still felt generally warm enough in my home. And around the compound a few developments have taken place as well: the gorgeous maroon and yellow and deep blue winter flowers have bloomed; Mrs. Iftikhar – this is what Hussain calls her and I’m either not bold enough or too frightened to ask her her name – has become imperiously queen-like: ignoring me if I’m at her door asking for her husband, boldly strolling into my house unannounced to go upstairs and retrieve some knickknack or use the bathroom to wash her hands (apparently only my bedroom/living space is considered mine, the remainder of the house I live in is for all and sundry. This was not in the lease. Oh, that’s right, there is no lease.); and Tom, my pet stray cat, now feels comfortable enough to come into my room and sit and watch me eat from a few feet away, awaiting the chicken bones that are sure to be passed down. I am still not allowed to touch him, however.

But just before dinner, as a rainy chilly day turned misty evening then bone-chilling night and I put my wool cardigan on over my zipper hoodie, which was already on over another sweater and a t-shirt, winter arrived. And as I finished dinner and let Tom have at his bones outside rather than in, so I could shut the doors to keep out the chill, I saw it. Literally. Right there in front of my face as I opened a book. Hovering and vaguely opaque. It looked like smoke but I wasn’t smoking. And then it hit me. It was my breath.

And so I begin to understand. In Kashmir the winter will not be kept away with the shutting of a door and pulling closed of a window. It is a season, just like any other, and when it comes, it’s everywhere, in our kitchens and bathrooms, our living space and our bedrooms, and for five months or so, we must grin and bear it.

I’m cold, sure, but also rather excited.

Hello, again. I haven’t updated in a while not because I’ve been too terribly busy but more because nothing terribly noteworthy had happened. Sure, I took a little detour to Turkey, which was really something, and just before that I enjoyed a wonderful dinner celebration for Agha’s 84th birthday, an evening during which I chatted with an amiable Delhi University professor who’d been tortured for thirty days and then sat on death row for about a year. But nothing really smashing, at least in my mind. Or maybe I’ve just been lazy.

Either way, the torporing doldrums ended this evening shortly after dinner. But first I have to back up a bit. Ever since I began to even consider the possibility of moving to and living in Kashmir I had heard tell of its fierce winters, of bitter cold nights that lasted a lifetime, of entire villages buried in snow, of roads closed, of frozen guns unable to fire, of the long-winded trials of a frigid Himalayan season in a region without indoor heating. Upon hearing that I planned to live in Kashmir an entire year, Rafiq Kathwari, a Kashmiri journalist cum photo-documentarian who now spends much of his time in New York, bluntly warned: “You’re staying there during the winter? You will die.” But as September waned the days were still warm, and then October brought little change: the sun still shone nearly every day and even if the nights had grown chilly the rising of the mercury became as reliable as that of the sun. That is until these last few days. The sun has taken a siesta. The Kashmiri pheran, a long, roomy dun-colored overcoat-poncho, has become ubiquitous. By the time I arrive home from work in the evenings after the ten minute bike ride my hands are nearly numb. And then this morning I saw a man maneuvering something unseen under his pheran, and when I walked closely past him I felt its warmth: a kangri! The mythical earthenware pot that Kashmiris hold underneath their outer coverings during the winter months, it holds perennially burning coals and is generally a substitute for what the developed world all but ignores: heating. The slang term is winterwife, a phrase that sounds much more pregnant in Kashmiri. But these things I shrugged off, girding myself for what still lie ahead. (And truth be told I haven’t heard a temperature number in months. But even if I had, it’s in Celsius, so 13, for instance, what does that mean? Sure, I could do the math, but I know offhand that it’s not the 13 of a Wisconsin November, I can tell you that much. It’s just nicely nestled in there somewhere between hot and cold, between pleasant and less so, between summer and winter. Cool. Sweater weather, as they say.) And of course I still felt generally warm enough in my home. And around the compound a few developments have taken place as well: the gorgeous maroon and yellow and deep blue winter flowers have bloomed; Mrs. Iftikhar – this is what Hussain calls her and I’m either not bold enough or too frightened to ask her her name – has become imperiously queen-like: ignoring me if I’m at her door asking for her husband, boldly strolling into my house unannounced to go upstairs and retrieve some knickknack or use the bathroom to wash her hands (apparently only my bedroom/living space is considered mine, the remainder of the house I live in is for all and sundry. This was not in the lease. Oh, that’s right, there is no lease.); and Tom, my pet stray cat, now feels comfortable enough to come into my room and sit and watch me eat from a few feet away, awaiting the chicken bones that are sure to be passed down. I am still not allowed to touch him, however.

But just before dinner, as a rainy chilly day turned misty evening then bone-chilling night and I put my wool cardigan on over my zipper hoodie, which was already on over another sweater and a t-shirt, winter arrived. And as I finished dinner and let Tom have at his bones outside rather than in, so I could shut the doors to keep out the chill, I saw it. Literally. Right there in front of my face as I opened a book. Hovering and vaguely opaque. It looked like smoke but I wasn’t smoking. And then it hit me. It was my breath.

And so I begin to understand. In Kashmir the winter will not be kept away with the shutting of a door and pulling closed of a window. It is a season, just like any other, and when it comes, it’s everywhere, in our kitchens and bathrooms, our living space and our bedrooms, and for five months or so, we must grin and bear it.

I’m cold, sure, but also rather excited.

9.28.2006

It's Nothing. Really.

Leaving home for work yesterday morning I had to stop in the alley leading to the main road because two men were blocking my path, chatting amicably as one straddled a gun-metal gray Vespa. Angry shouts suddenly rang out from behind, from where I’d come, and a blazing-eyed young man wearing green pants sped around the corner on his Vespa, stopped nearly on the other Vespa driver’s shoes and yelled in his face, accusatorily, condemning, cursing, and he grabbed his collar and shook the smaller man. Then just as I squeezed by green pants cocked his right arm, once twice, and let fly a punch into his offender’s jaw. Grabbing each other’s shirts and shaking the two clambered off the scooters and started to wrestle, still shouting, bringing men from nearby doorways and alleys, some trying halfheartedly to separate them and others watching with concern, interest, indifference. At one point the green pantsed man was getting the better of the other and the two were separated, venomous words spitting across the meter-wide divide. Then, queerly, a smallish oval was cleared and the inflamed duo were left to their passions, a chicken fight christened. The two danced unpredictably in the dirt for a few seconds then pounced simultaneously, twisting and grimacing. Finding a free arm, smaller black shirt got in a couple good shots from close range, enraging the bigger green pants.

Out of my peripheral vision stepped an older gent, who came close, amiably, as if we were at the zoo or the circus, “Hello, Sir! And where are you going?” he smiled broadly, gesturing towards my motorbike. “Uhh,” I responded, grasping now the meaning of the word desensitized. “What are they fighting about?”

“Huhnph?” he queried, not knowing to what I was referring. “Oh, this,” and he smiled the smile of the older and wiser as if it were boys being boys, ”Oh, it’s nothing. Where are you from?”

Green pants had his black-eyed and bloodied opponent in a solid headlock and eyed the brick wall, at which point saner heads stepped in. And from violence back we swung back to urgent diplomacy, the two men breathing heavily with reddened faces and rent clothing,staring daggers, green pants still incensed about some great offense the other embarrassed to be so thoroughly thrashed and, if his eyes were any indication, still 1intent on revenge. The scene appeared to be calming when suddenly another young man flew in from nowhere – my right, actually, where I and green pants had come from – and started punching black shirt, which sparked an entirely larger and more complicated ruckus. Suddenly there were four or five combatants, somebody’s head was very nearly thumped into the wall, and a white shirted deviant picked up a softball-sized chunk of black pavement and bashed it into the head of black shirt. I stepped in and separated those two and coralled black shirt from behind to make sure he was OK, which he was generally, although woozy and with the eyes of a frightened animal, red molasses dripping from his dark curly hair. Stuck in survival mode, he wheeled as if to punch me but stopped short upon seeing my face.

Passions waned. Black shirt waved off aid and suggestions of the hospital, green pants was led back to his waiting, prone Vespa, and the white shirted lunatic stared into and kicked the dirt in the face of a gentle talking-to from a white-capped older gentlemen.

My new friend smiled. “It’s OK, it’s OK,” he said. “This is Kashmir.”

Out of my peripheral vision stepped an older gent, who came close, amiably, as if we were at the zoo or the circus, “Hello, Sir! And where are you going?” he smiled broadly, gesturing towards my motorbike. “Uhh,” I responded, grasping now the meaning of the word desensitized. “What are they fighting about?”

“Huhnph?” he queried, not knowing to what I was referring. “Oh, this,” and he smiled the smile of the older and wiser as if it were boys being boys, ”Oh, it’s nothing. Where are you from?”

Green pants had his black-eyed and bloodied opponent in a solid headlock and eyed the brick wall, at which point saner heads stepped in. And from violence back we swung back to urgent diplomacy, the two men breathing heavily with reddened faces and rent clothing,staring daggers, green pants still incensed about some great offense the other embarrassed to be so thoroughly thrashed and, if his eyes were any indication, still 1intent on revenge. The scene appeared to be calming when suddenly another young man flew in from nowhere – my right, actually, where I and green pants had come from – and started punching black shirt, which sparked an entirely larger and more complicated ruckus. Suddenly there were four or five combatants, somebody’s head was very nearly thumped into the wall, and a white shirted deviant picked up a softball-sized chunk of black pavement and bashed it into the head of black shirt. I stepped in and separated those two and coralled black shirt from behind to make sure he was OK, which he was generally, although woozy and with the eyes of a frightened animal, red molasses dripping from his dark curly hair. Stuck in survival mode, he wheeled as if to punch me but stopped short upon seeing my face.

Passions waned. Black shirt waved off aid and suggestions of the hospital, green pants was led back to his waiting, prone Vespa, and the white shirted lunatic stared into and kicked the dirt in the face of a gentle talking-to from a white-capped older gentlemen.

My new friend smiled. “It’s OK, it’s OK,” he said. “This is Kashmir.”

9.23.2006

Bharat, A Confused Kashmiri Tradition

This is a Shia holiday that honors the anniversary of the birthday 12th imam, a key historical figure for Shia Islam. It is a sort of a day of the dead, when Kashmiris mourn the recently or long ago deceased by placing candles on their flat-laying tombstones. One would envision a solemn occasion, and from these pictures it might appear to be, but for some strange reason it is also part 4th of July, and the celebrants, especially the younger ones, set off dozens and dozens of firecrackers, tossing them wherever they wish and creating a grating cacophony.

As I was taking this first picture on the roof of a pavilion overlooking the cemetery some bright youngster threw a pack right between my legs – Pow! Puh-puh-pu-puh-pu-Pow-POW! And of course I jumped and started to yell at them but they laughed it off and nobody much seemed to mind. I pretty much shrugged it off, but you know what, celebrating is one thing and setting miniature explosives to a man’s crotch is quite another. Anyway, I crawled down from the roof and kept snapping, but I could only get this single quality shot because a crowd of ankle-biters quickly gathered in a train behind me and disturbed every solemn moment on which I choose to focus. The firecrackers also became a bit much so I trudged home scratching my head.

9.17.2006

Indian Efficiency

So I had asked this first guy from UNESCO if he could give me contact info for someone on the World Heritage Committee, which he then sent. i think you can read the rest for yourself, as this Batra character does an excellent impersonation of a robot.

Perhaps you mean the World Heritage Committee. India is currently a member (until 2007) and I am giving below the contacts of the delegate who attends the meetings of the WH Committee and with whom you can speak about WH issues:

Mr. C. Babu Rajeev

Director General and Additional Secretary

Archaeological Survey of India

Ministry of Culture, Government of India

Janpath, New Delhi – 110011

E-mail: dgasi@vsnl.net

Tel: 23013574

8/29

Mr. Rajeev --

Hello, my name is David Lepeska, senior correspondent for the Kashmir Observer in Srinagar, Kashmir, India. I've been writing about the possibility of Dal Lake being nominated and getting inscribed as a World Heritage site. I'm writing to ask if I might ask you a couple questions about the work of the WH Committee and whether Dal Lake might be a legitimate possibility for inscription.

Please consider and let me know soon, and I will send questions via email or give you a call, whichever you prefer.

Thanks

David

Sir,

Please refer to your email dated August 29, 2006 on the above subject. In this connection, you may get in touch with PS to DG, ASI for appointment.

DG's office

PS to DG? What is that?

Thanks,

DavidSir,

Please refer to your email reg. Dal Lake. In this connection, you may please contact Private Secretary to Director General, Archaeological Survey of India for appointment.

DG's office

sir, you work in the DG's office, yes? perhaps then you could either help me set up a chat or provide me with the private secretary's contact information. please.

thanks,

david

Dear Mr. David Lepeska,

Please refer to your earlier emails addressed to Mr. C.Babu Rajeev, DG, ASI. It has been desired by DG, ASI that you may seek prior appointment with him and meet him in person in Delhi regarding your subject. DG, ASI is out of India till 17th of this month and will be back in office from 18th September 2006 onwards. In case you wish to meet DG please let us know so that a mutually convenient date and time is fixed.

Regards,

Sanjeev Batra

Secretary to DG, ASI

Sanjeev --

As I pointed out above, I'm in Srinagar, so a Delhi meeting is highly unlikely. Could I either email or call him shortly after his return? Perhaps you could advise an appropriate time.

Thanks,

David

Dear Mr. David Lepeska,

I shall inform DG, ASI about your difficulty in coming to Delhi on his return from tour and revert back to you. In the meantime you may like to email your contact telephone no. in the event of connecting DG, ASI to you over telephone.

Regards,

Sanjeev Batra

Perhaps you mean the World Heritage Committee. India is currently a member (until 2007) and I am giving below the contacts of the delegate who attends the meetings of the WH Committee and with whom you can speak about WH issues:

Mr. C. Babu Rajeev

Director General and Additional Secretary

Archaeological Survey of India

Ministry of Culture, Government of India

Janpath, New Delhi – 110011

E-mail: dgasi@vsnl.net

Tel: 23013574

8/29

Mr. Rajeev --

Hello, my name is David Lepeska, senior correspondent for the Kashmir Observer in Srinagar, Kashmir, India. I've been writing about the possibility of Dal Lake being nominated and getting inscribed as a World Heritage site. I'm writing to ask if I might ask you a couple questions about the work of the WH Committee and whether Dal Lake might be a legitimate possibility for inscription.

Please consider and let me know soon, and I will send questions via email or give you a call, whichever you prefer.

Thanks

David

Sir,

Please refer to your email dated August 29, 2006 on the above subject. In this connection, you may get in touch with PS to DG, ASI for appointment.

DG's office

PS to DG? What is that?

Thanks,

DavidSir,

Please refer to your email reg. Dal Lake. In this connection, you may please contact Private Secretary to Director General, Archaeological Survey of India for appointment.

DG's office

sir, you work in the DG's office, yes? perhaps then you could either help me set up a chat or provide me with the private secretary's contact information. please.

thanks,

david

Dear Mr. David Lepeska,

Please refer to your earlier emails addressed to Mr. C.Babu Rajeev, DG, ASI. It has been desired by DG, ASI that you may seek prior appointment with him and meet him in person in Delhi regarding your subject. DG, ASI is out of India till 17th of this month and will be back in office from 18th September 2006 onwards. In case you wish to meet DG please let us know so that a mutually convenient date and time is fixed.

Regards,

Sanjeev Batra

Secretary to DG, ASI

Sanjeev --

As I pointed out above, I'm in Srinagar, so a Delhi meeting is highly unlikely. Could I either email or call him shortly after his return? Perhaps you could advise an appropriate time.

Thanks,

David

Dear Mr. David Lepeska,

I shall inform DG, ASI about your difficulty in coming to Delhi on his return from tour and revert back to you. In the meantime you may like to email your contact telephone no. in the event of connecting DG, ASI to you over telephone.

Regards,

Sanjeev Batra

9.15.2006

Moving Day on Dal Lake

The Queen of Residency Road

Can a beggar be beautiful? Well, I guess some would say that every human being is beautiful, but I'm talking about actual physical appearance. Most would say no, and in the US they would be right, at least as far as I can tell. But this woman, who walks up and down Residency Road with a child or two in tow and usually one in her arms, is just gorgeous, with mocha skin and powerful eyes and nice features. And she knows it, too. I couldn't figure it out until I noticed that she's pretty darn healthy looking, and so are her kids, one of which is very young, as you can see by this pic, and I bet that she has a husband, perhaps Bihari, who works a day job and makes a decent wage. And that she just does this for some extra spending money. Maybe not, but either way, the way she smiles, shames, and flirts the men of Srinagar into giving is something to see.

Can a beggar be beautiful? Well, I guess some would say that every human being is beautiful, but I'm talking about actual physical appearance. Most would say no, and in the US they would be right, at least as far as I can tell. But this woman, who walks up and down Residency Road with a child or two in tow and usually one in her arms, is just gorgeous, with mocha skin and powerful eyes and nice features. And she knows it, too. I couldn't figure it out until I noticed that she's pretty darn healthy looking, and so are her kids, one of which is very young, as you can see by this pic, and I bet that she has a husband, perhaps Bihari, who works a day job and makes a decent wage. And that she just does this for some extra spending money. Maybe not, but either way, the way she smiles, shames, and flirts the men of Srinagar into giving is something to see.

9.12.2006

The Bully and the Bruised, the Slingshot and the Stone

One American's Abridged Post-9/11 History

On a gorgeous Tuesday morning five years ago I stood with several co-workers on the roof of an office building in downtown Manhattan and watched in stunned silence as the south tower of the World Trade Center collapsed, sending great khaki-colored plumes of smoke, dust, and debris shooting across the southern tip of the island. In a daze I drifted to the stairs and out of the building, stepping into a Gothic scene. Dust covered zombies shuffled up from Ground Zero, stopping to catch their breath and stare into the middle distance, eyes wide and mouths half-opened. Buzzing crowds gathered around storefront televisions and radios on Broadway, yearning for the whos and hows and whys while others embraced and conferred in desperate tones. Attacked on its own turf unawares, New York, and America, had been shocked and deeply wounded, and something had to be done.

You might recall the outpouring of sympathy from across the globe (or you may not). Parisian headlines carried condolences and in Germany 200,000 gathered at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate to express their sorrow. Palestinians held not one but two candle-lit vigils and in Tehran's largest stadium 60,000 soccer fans and players observed an unprecedented minute's silence in sympathy with the victims. French political analyst Nicole Bacharen summed up the solidarity that swept the world: "At moments like this, we are all Americans."

"International notes of sympathy and empathy are fine,” Rand analyst James Mulvenon responded prophetically at the time. “But what will separate those who are with us from those who are against us is military action."

And so it has passed that the bellicose rhetoric and mostly unjustified, Islam-trained aggression of American foreign policy that followed has erased that great goodwill and exacerbated already-extant tensions with the Muslim world. Numerous major terror attacks and the combative belligerence and often ignoble proclamations on the part of Muslim leaders have also fanned these fires, and, as a result, the intervening five years have left that 21st century sword of Damocles, the long-feared clash of civilizations, hanging by a thread.

The Trouble Deepens

When the U.S. sought to retaliate that October with the toppling of Afghanistan’s Taliban, most developed nations were behind the move. Syria, North Korea, and Iran predictably sounded the first discordant notes, and as the US’ widespread and seemingly indiscriminate bombing raids led to vast civilian deaths condemnations poured in from the United Nations, Oxfam, and Doctors Without Borders, prodding Donald Rumsfeld to trot out that infamous term of obfuscation, “collateral damage,” and signaling the great tides of diversionary rhetoric soon to flow from the Bush administration.

But if Afghanistan was a grenade to global American approbation, the invasion of Iraq was an atomic blast. The Bush team linked then-Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein to Al Qaeda and claimed he had great stockpiles of weapons capable of mass destruction, both of which represented imminent threats to the United States and both of which history has since Swiss-cheesed. In a reversal of post-9/11 solidarity, protest marches from New York to Chicago, London to Paris, Damascus to Sydney, Tokyo to Milan and beyond, tens of millions of demonstrators expressed vehement opposition to the US’ planned preemptive war. France and Germany, which had so eloquently shared New York’s sorrow, stood out as America’s most vocal detractors. Yet shock and awe was unleashed on Iraq in March 2003, a point in time future historians may mark as the beginning of the end for American hegemony.

The World Today

Recent developments in five key stories traceable to 9/11 provide an excellent overview of the current global situation.

1. Rising sectarian violence has reached a new post-invasion peak in Iraq, with a fifty-one percent rise in casualties among Iraqis in the past three months alone and more than 3,000 killed each month, according to a US Defense Department report released last week. “This is reality catching up with Rumsfeld and the Pentagon,” said Brookings Institution military analyst Michael O’Hanlon. Where there was once no Al Qaeda, the cells are now legion, prodding Bin Laden to dub the struggle in Iraq the “third world war…a war of destiny between infidelity and Islam. The whole world is watching this war and it will end in victory and glory or misery and humiliation.” Far from the stable democracy Bush, Rumsfeld, Cheney and the neo-conservatives envisioned, Iraq is embroiled in a civil war with global ramifications.

2. Afghanistan’s 2006 poppy crop, estimated last week by the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime at a record 6100 metric tons of opium, or ninety-two percent of world supply, is certain to please heroin addicts, poppy farmers, and the warlords expecting a piece of the action. This is an increase of nearly sixty percent from 2005 for a trade that accounts for over one third of Afghanistan’s economy and continues to bankroll insurgent elements. Five years after the toppling of the Taliban, three years into the Hamid Karzai regime, and months after NATO took over security responsibilities from coalition forces, the Taliban is resurgent and much of Afghanistan is a warlord-ruled, chaos-rife narco-state. Oft-lauded US anti-terror ally Pakistan essentially ceded parts of its Afghan-bordering North Waziristan province to the Taliban and Al Qaeda in a just-inked truce, giving Osama bin Laden and his co-horts their own private mountain redoubt. "This country could be taken down by this whole drugs problem," the U.S. top narcotics official admitted. "We have seen what can come from Afghanistan, if you go back to 9/11. Obviously the U.S. does not want to see that again."

3. For most of the Muslim world, this summer’s Israeli-Lebanon war was a shorter, more satisfying sequel to the Afghanistan-USSR conflict that ended the Cold War. Islamic radicals fought and essentially defeated a great global power, even if by proxy, and a charismatic, militant, devoutly Muslim leader (bin Laden then, Hezbollah's Hassan Nasrallah today) stood up to a regional and international bully, sending his status through the roof. The fallout included an Israeli investigation into military failures, a Saudi Arabia that had urged other Arab states to be careful of Hezbollah when the Israel-Lebanon crisis was brimming suddenly dissatisfied with the U.S., and the exact opposite of stated intentions – a more vigorous Hezbollah and Iran. The over one thousand Lebanese casualties brought accusations of war crimes from the UN and increased international opprobrium.

4. Opinion within the US reveals increasing disapproval of the Bush administration and its war on terror, as over half of Americans support neither the Iraq War, their president, nor the linkage between Saddam and Al Qaeda. In an online interview this week, Pulitzer Prize-winning New Yorker journalist Seymour Hersh said, “By going to war, instead of criminalizing what Osama bin Laden and his minions did—there’s no question that, in terms of military operations, this is the worst government in the history of America.” As if on cue, the World Citizens Guide, a pamphlet recently published by the Texas-based nonprofit Business for Diplomatic Action in the hope of ameliorating anti-Americanism, blithely underscores the faults of US’ post-9/11 leadership. The document offers Americans traveling abroad diplomatic insights the American president could take to heart: dialogue instead of monologue; be proud, not arrogant; check the atlas; talk about something besides politics; and keep your word.

5. Polling data published recently by Harris and the Pew Global Attitudes Project reveals considerable drops in US esteem across Europe and the Middle East. Out of the five most powerful European nations, according to the Harris Poll, only Italians believe the US is not the greatest threat to global stability. And overall polling data found that nearly twenty-five percent more pollsters believed the US more dangerous than Iran. Since 9/11, outbreaks of Muslim violence, deadly terror attacks, and/or major arrests have occurred in the UK, the Netherlands, Spain, France, Germany, and just this past week authorities arrested accused plotters in Denmark – Europeans may well blame these new problems with recent US foreign policy. Less than one quarter of Spain’s populous holds a favorable opinion of the US, according to Pew, and Turkish regard has dropped from over half to a mere twelve percent.

Turkey Turns Away

Often cited as the very type of democratic, secular, and Muslim nation the US would like to import to the Middle East, Turkey has long served as vibrant evidence of the Western argument that Muslim nations could willingly and successfully embrace democratic institutions. But this bridge between the West and the Muslim world is crumbling, mainly because of American foreign policy, making Turkey the new poster boy for the world’s post-9/11 attitudinal adjustment.

Since the American-led and UK-supported invasion of Iraq, the Turks have turned away not only from the U.S. but from long-sought EU-membership. Instability in its mainly Kurdish southeast, which borders the predominantly Kurdish northern-most province of Iraq, has ignited separatist sentiments among Turkey’s 15 million Kurds. Turkish leaders fear chaos in Iraq could lead to renewed calls for an independent Kurdistan, with the blame placed squarely on American shoulders.

The latest Transatlantic Trends survey, released last week, confirms this development. Favorable U.S. opinion has dropped twenty-five percent in the past two years while views of Iran have received a similar bounce in the same span. Perhaps even more telling is the data regarding Iran’s tough stance on the nuclear issue: approximately forty percent of Americans and Europeans approve of the use of force to keep Tehran from getting nuclear weapons, compared to only ten percent of Turks polled, more than half of whom approved of an Iran with nuclear weapons. These figures become more chilling considering that in his landmark work, “The Clash of Civilizations and the Coming World Order,” Samuel Huntington cited Turkey as a potential barometer of West-Islam relations. “At some point, Turkey could be ready to give up its frustrating and humiliating role as a beggar pleading for membership in the West and to resume its much more impressive and elevated historical role as the principal Islamic interlocutor and antagonist of the West.” That time may be nigh.

Fighting the Bad Fight

How have we arrived at such a tangle of crisscrossing anguish? One reason is America’s military aggressiveness, to be sure, but its tin ear, which invariably results in uninformed rhetorical bombast, does not help. In a speech in Washington last week Bush reiterated his latest theme: “Bin Laden and his terrorist allies have made their intentions as clear as Lenin and Hitler before them. The question is: Will we listen? Will we pay attention to what these evil men say? America and our coalition partners have made our choice. We're taking the words of the enemy seriously. We're on the offensive. We will not rest. We will not retreat. And we will not withdraw from the fight until this threat to civilization has been removed.”

This is a slightly different iteration of Bush’s post-9/11 “for us or against us” paradigm, which reduces the world to black and white, good and evil, painting people as either secular, democratic and Western-leaning or wrong-headed, fascist and terror-plotting, whereas in reality over half the world’s population fall somewhere in between. The fascist analogy has been torn to shreds elsewhere, and the reference to communism not only brings to mind precisely the kind of global conflict the US should seek to avoid but also links today’s terrorists with an ideologically powerful popular revolt that controlled a large chunk of the world for some 70 years. One of the primary goals of any terrorist group is getting their opponents to overestimate their importance, and here once again is Bush falling into that trap. What’s more, a US on the offensive is precisely what Islamic terrorists want, Americans playing the bully, the big kid on the block who knocks around his smaller neighbors; the belligerence and the resulting death count are excellent recruitment tools.

“For decades,” Bush continued, “American policy sought to achieve peace in the Middle East by pursuing stability at the expense of liberty. The lack of freedom in that region helped create conditions where anger and resentment grew and radicalism thrived and terrorists found willing recruits.” Yet America’s universalist pretensions, its continued reliance on military means, and a surfeit of dead Muslims are creating those same conditions today.

Indeed, the Bush team and its allies have since 9/11 sought to drive their enemies into submission by hitting them atop the head with a stone. The blunt objects of traditional warfare – technologically advanced as Bradley fighting vehicles, killer drones, and laser-guided cluster bombs may be, they are but bombs, planes, and tanks – have not only wrought immeasurable physical damage on the infrastructure, humanity, and psyche of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Lebanon, but have also provided great grist for the terrorist mill. At least 100,000 dead civilians in Iraq and increasing local animus with inadequate NATO forces in Afghanistan do nothing to bolster the image of America in the Muslim world. And the pictures of slaughtered Lebanese civilians that shot around the globe in July and August were a public relations bonanza for Hezbollah that contributed significantly to leader Hassan Nasrallah’s burgeoning esteem.

Al Qaeda, meanwhile, has consistently endeavored to build the better slingshot. Call it cowardly if you must, but hijacking planes and using them as giant missiles was a brilliant tactical innovation. And the recently uncovered UK terror plot in which operatives had planned to combine several innocuous fluids to build bombs while in flight revealed a terrorist network constantly looking for new and unpredictable means of destruction.

Much of the reasoning behind stodgy American policy can be found in the White House’s newly-updated National Strategy for Combating Terror (available in full at www.whitehouse.gov), which argues “the long-term solution for winning the War on Terror is the advancement of freedom and human dignity through effective democracy… Effective democracies honor and uphold basic human rights, including freedom of religion, conscience, speech, assembly, association, and press...are responsive to their citizens, submitting to the will of the people. Effective democracies exercise effective sovereignty and maintain order within their own borders, address causes of conflict peacefully, protect independent and impartial systems of justice, punish crime, embrace the rule of law, and resist corruption…They are the long-term antidote to the ideology of terrorism today. This is the battle of ideas.”

More than a decade ago Huntington warned of precisely such efforts, writing that these same ideals “make Western civilization unique, and Western civilization is valuable not because it is universal but because it is unique. The principal responsibility of Western leaders, consequently, is not to attempt to reshape other civilizations in the image of the West, which is beyond their declining power, but to preserve, protect, and renew the unique qualities of Western civilization.”

President Bush has done just the opposite since taking office – spending lavishly on foreign wars, slashing taxes, and overextending his armed forces in supporting a new and more aggressive form of American exceptionalism. Like a Rip van Winkle who dozed off at the dawn of the Clausewitzian era, the Bush team has blindly maintained its reliance on military might to impose their will even as Europeans and Americans have begun to apprehend vast cultural differences. The Transatlantic Trends survey shows only one-third of Americans and a mere quarter of Europeans support the use of military force in promoting democracy abroad. What’s more, fifty-six percent of Americans and Europeans believe their form of democracy is not compatible with Islam.

This weakened US, then, is in for a long slog, not only because Islamic societies are inherently different from the West, but more importantly because they intend to stay that way. Regardless of its sectarian form, the reaffirmation of Islam exploding across the earth’s mid-section is also a repudiation of Western influence upon local politics, society, and morals.

A Dearth of Good Leadership

As this Islamic resurgence is not entirely open-minded and benevolent, the blame for the current loggerheads cannot be placed solely at the feet of the US. Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad and Hezbollah’s Nasrallah, who in the past year have risen to pre-eminence in the Muslim world, the former for his defiance of the West in regards to nuclear armament and the latter for beating back an Israeli army long viewed as an unstoppable regional juggernaut, have played key roles in bringing the world closer to the brink.

Although the recent Israeli bombardment of south Lebanon may well have been disproportionate, pronouncements such as the following make it difficult for a sober-minded 21st century adult to join Hezbollah’s fight: “We will win because the Jews love life,” said Nasrallah in early August, “and we love death.” Similar words had been uttered previously by bin Laden and his terror-minded ilk, but these were so patently unnecessary and obviously inaccurate as to make one question Nasrallah’s sincerity, if not sanity. If you love death than why did you not embrace it when Israelis offered it to you on a platter? August news reports from New York to Mumbai were reporting how the Arab street and the Muslim tide had swelled behind Hezbollah and its increasingly powerful and popular leader. Why? Because Hezbollah had been so staunch and stealthy in the face of Israeli aggression, because they had fought well and survived, embracing life. Nasrallah later clarified his remark: “Regardless of how the world has changed after 11 September, death to America will remain our reverberating and powerful slogan, 'Death to America.'" This specifies the very sort of death Hezbollah loves, but it is not a statement from which harmony and understanding might flower.

Similarly, Ahmadinejad delivered this message to the American people in July: "If you would like to have good relations with the Iranian nation in the future, bow down before the greatness of the Iranian nation and surrender. If you don't accept to do this, the Iranian nation will force you to surrender and bow down." And now the Iranian president is bent on an ideological cleansing, purging his nation’s colleges and universities of all liberal and secular professors.

That Nasrallah and Ahmadinejad are in cahoots is not surprising, but one would hope the Islamic resurgence could hang its hat on more cogent, sober and inspiring words of wisdom. Where is the Mustafa Kemal Ataturk for this century?

Neither is it a surprise that these two can make such dull and blandly ignorant statements as those above and still be as revered as they are in the Muslim world, by both extremists and moderates. Because they stood up to Israel, and particularly the U.S., the country that attacked and decimated Iraq unjustifiably, in violation of the UN and against the wishes of millions. Further, bruised by the end of the Caliphate five hundred years ago and subsequent centuries of imperialism, subjugation, and West-backed autocracies, a deeply rooted animus towards the US and Britain is burned into Muslim hearts. In the last five years the US, UK, and Israel have merely fanned the embers.

Osama bin Laden has for his part stepped back from the spotlight in recent years, increasingly ceding MC duties on Al Qaeda’s regular video releases to his second in command, Ayman Al Zawahiri. The leading terror organization even tapped a former infidel, converted American Jew Adam Gadahn, to deliver its most recent message in early September. In the video, Gadahn urged Americans to "surrender to the truth,” convert to Islam, and "join the winning side.” One is reminded of the rhetoric of the leader of Gadahn’s homeland.

The lone voice of eloquent near-reason has been British Prime Minister Tony Blair, but riding shotgun with Bush and American foreign policy has compromised his position and erased what understanding he may have engendered in the Muslim world. The UK has thus emerged as Europe’s top terror target and almost three-quarters of recently polled British believed the nation’s foreign policy is to blame, prodding Blair to announce last week that he will resign in late spring 2007.

In this war, then, no promising leader has emerged from any quarter. Instead of reason, restraint, and understanding, we have insults, threats, and ignorance. Two goons brawling in a back alley, a bar fight between drunken belligerents, one angry and dimunitive and occasionally crafty, the other a lumbering, thick-skulled ox attempting a lobotomy with a crowbar. Is it to this we have evolved? Is this how the world ends?

Shifting Gears, Moving Forward

In increasingly tense times, a look to two historical anniversaries of peace may help light the way.

One hundred years ago to the day – September 11, 1906 – an Indian lawyer working in South Africa kick-started a movement that would change the world. At a political meeting in Johannesburg, Mohandas K. Gandhi took from his countrymen the first oaths of what would become satyagraha, literally a firmness in truth but more accurately a categorical commitment to nonviolent resistance. I’m not so idealistic as to expect international relations to become a forum for Gandhian nonviolence, but leaders of Islam and the West would be wise to consider the Mahatma’s philosophy: “the nonviolence of my conception is more active and more real fighting than retaliation, whose very nature is to increase wickedness.” India’s sober response to the July bomb blasts in Mumbai, which could certainly inform both Western and Islamic policymakers, bear out this belief.

And fifty years ago a Canadian diplomat serving at the U.N. helped defuse Western-Islam animus when he brokered an agreement between the U.S., Europe, Israel, and Egypt to end the crisis over the Seuz canal. Lester Pearson, who later served two terms as Canadian Prime Minister, won a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts, with the Nobel panel claiming he had “saved the world.” One could be sure that realizations such as the following, uttered years previous, played a part. “It would be absurd to imagine that these new political societies coming to birth in the East will be replicas of those with which we in the West are familiar; the revival of these ancient civilizations will take new forms.” It is precisely such new forms that the West must be willing to accept, for our divergences are integral to our civilizations.